In an interesting article called How the Power of Interest Drives Learning, Annie Murphy Paul says

Parents, educators and managers can also promote the development of individuals’ interests by supporting their feelings of competence and self-efficacy, helping them to sustain their attention and motivation when they encounter challenging or confusing material.

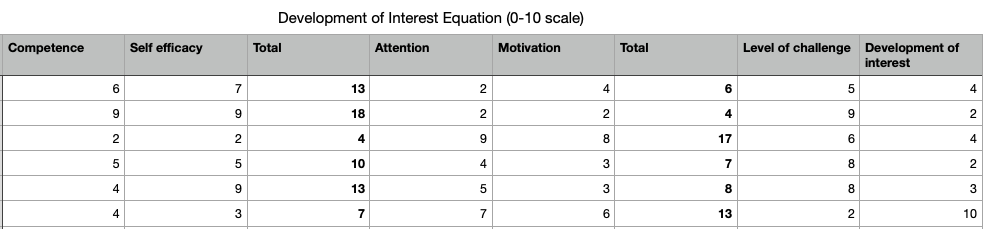

Let’s have a bit of fun and turn that claim into a maths equation.

(Feelings of competence + self-efficacy) + (attention + motivation) / challenging material = development of interest.

What determines those factors?

Take feeling competent. Sure, there’s an element of ‘skill and drill’ there, but not completely. There are plenty of things I’ve done over and over and still don’t feel competent doing. Conversely, there are things that come easy to me and I feel competent in with much less ‘effort’.

Self-efficacy is a central concept in Albert Bandura’s social cognitive theory. He argued there are four main elements that help develop self-efficacy: mastery experiences (ie, having opportunities to do something well), social modelling (ie, seeing others do things well), social persuasion (ie, others encouraging us to see we can do things well) and emotional or psychological feedback (ie, how we feel about our own ability).

What about attention? It’s not a static thing, and instead is vulnerable to significant levels of variation from things like our emotional state, hunger, relationships, stress, tiredness, etc. How does attention relate to and affect motivation, and vice-versa? Sometimes, we can be very attentive to something yet lose motivation. Why?

So, what’s a teacher to do then? Well, I played around with the equation and got these results as a random starting sample. Let’s assume the student rates their levels of competence, self-efficacy, attention and motivation out of 10, and the teacher judges the challenge level out of 10.

The biggest thing that sticks out here? If the level of challenge is too high there is a reduced impact on the development of interest. (Is this Vygotsky’s ZPD idea expressed in numbers?) However, the level of challenge can be increased if at least one side of the initial part of the equation is strong (ie, competence / self-efficacy or attention / motivation).

If we assume that the level of challenge is something a teacher has some degree of influence over, if not control, then the question becomes how do they get access to the information that allows them to set it at an optimum level? That is, how do they know where a learner’s competence, self-efficacy, attention and motivation sit? Does this formula suggest the best form of support a learner can get is the opportunity to engage with challenges at just the right level?

In other words, the data that makes a difference to a learner’s growth and the development of their interest is small data. Having ‘high standards’ and focusing on the learning being ‘challenging’ and ‘rigorous’ without attending to the small data is a bit like playing the drums without listening to what the other musicians are doing.

SMATA

A tool to help teachers, help students.

SMATA helps you to capture observations, understand learning trends, and encourage growth.