Cars can get us places quickly, but anyone who rides a bike knows it’s the better way to experience a place and a journey. Yes, bikes are slower. But you notice more. You stop more. You meet more people and have more interesting conversations. You get to build a fuller picture of the places and people between A and B.

There’s an openness to experience when getting about on a bike that isn’t there when you’re in a car.

In a car we want to get to B. The faster the better. And I don’t know about you, but often it feels like drivers will do anything to get there. The focus on the result - getting there - justifies the means. Anything goes.

Our schools have become like cars, racing kids from one achievement milestone to the next. In this race, there’s no time for building meaningful connections, no time for genuine relationships where people help each other.

Teachers are under pressure to do what it takes to get kids up to speed, to help them keep up and to ensure they don’t drop their learning pace.

Kids are under pressure.

There’s nothing democratic about that.

Instead, if we want school to be a democratic experience, we need our schools to be like getting about on a bike.

Upgrade to a paid subscription plan with the Christmas special, and get unlimited access to all Smata Bulletin content.

Offer available until 26 December.

In my time on a school board, we spent a lot of time looking at data. Always, it looked like this

or this

What great data sets they were! They told us, in wonderful detail, where kids sat in relation to the areas the school deemed to be important.

We loved it when there were heaps of kids performing at or above expectations early in the school year: evidence of accelerated achievement - educational nirvana!

Even better, we then got to ask questions about how the remaining kids were going to have their learning supported to ensure they were up to speed with things by the end of the year.

Actually, the sooner the better.

Education is all about acceleration and extension, after all.

And surely, if you care about kids and their futures, who can argue with that?

We didn’t stop to think about whether all this data told us anything about the kids.

My daughter loves to dance. She has the occasional day off school to spend it dancing, and she loves those days. She tells us all the time she’s not going to university, she’s going to dance school instead.

She can’t wait to go to college and choose dance as a subject so she can dance during the school day.

Not a lot of dancing happens at primary school. It’s not reported on either. It’s my hunch there’s no data about dance held by the school.

Why not?

Is there no time? Probably.

Is it not valued? I don’t think the school would say so, but then actions show what we prioritise, which shows what we value.

The fact is, literacy and maths take priority, and they have heaps of data about them.

To be successful at school, my daughter has to leave her love at the door and show how good she is at learning what the school has decided is most important.

The only conclusion is that dance is seen as something nice but inessential, despite it being a core part of who she is.

Inessential to whom?

It’s in the curriculum, after all.

This might read as a dig at her school - it’s not. What it is is a personal example of something that is replicated in most schools in the country.

I replicated it when I was on a board too.

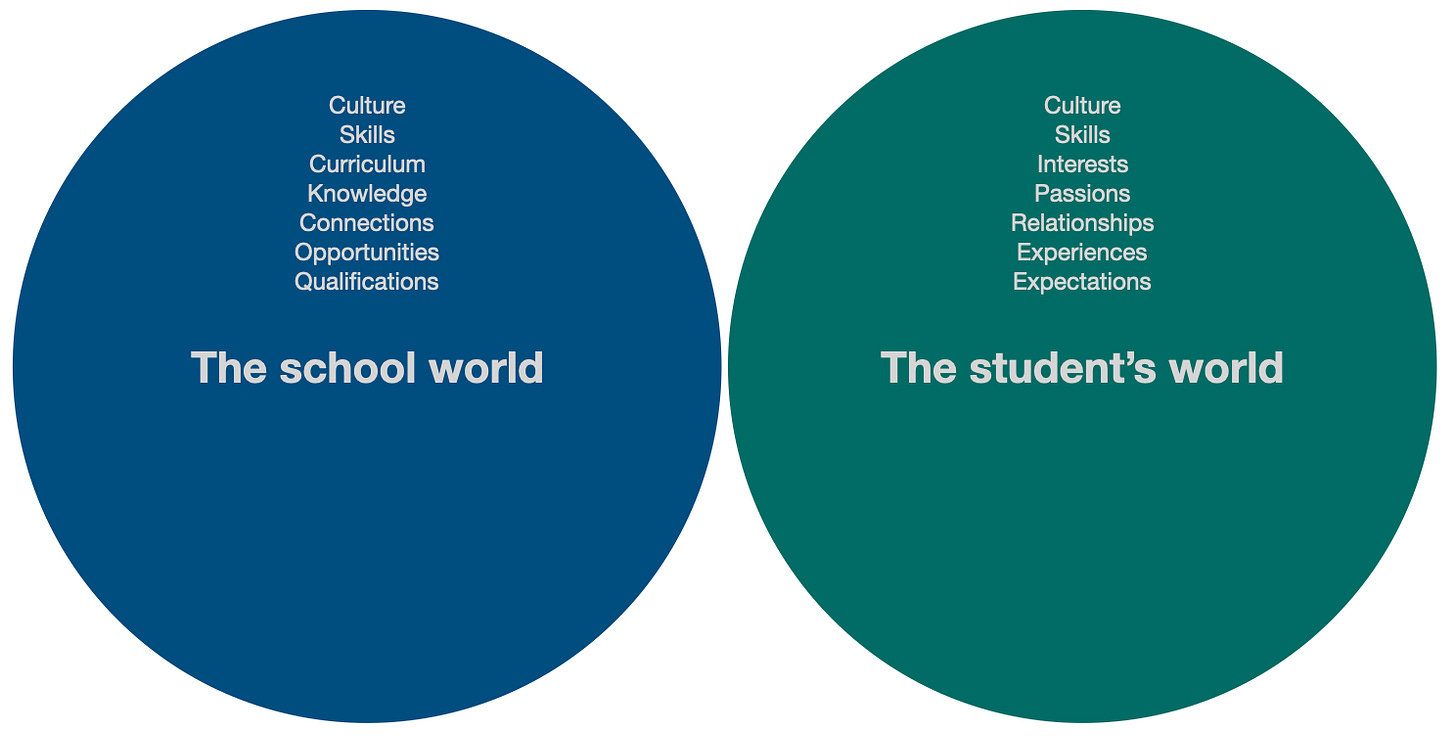

There are two worlds present in schools. These worlds are made up of a variety of different aspects, which may match/overlap to varying degrees.

Generally, the closer the match, the better the student is seen as being. Especially if they can show us proficiency in things valued in the school’s world. And if they can do this at a rapid rate, well, wow...

… we have an excellent student on our hands.

Is this a problem? I think so.

I think it sets up a dichotomy in schools, where one world is the more important, one less so, and it’s a barrier to the formation of democratic relationships.

There is no connection, just the dominance of the powerful.

Success is down to how well a kid ‘gets on’ with the more powerful.

The student’s world is swamped by the world of school.

There is no doubt that when the school world dominates and swamps the world of the student things become more efficient for the institution.

It means that when words like acceleration, extension and support get thrown about the adults know what to do because they’re done on their terms within a context that is familiar, safe to them, and narrow.

But we’re missing out on a whole lot of what’s valuable when we try to go at speed down smooth learning corridors.

Why is faster learning about two or three things want we want most of all?

“If we look at children only to see whether they are doing what we want or don’t want them to do, we are likely to miss all the things about them that are the most interesting and important”

John Holt, Why Children Fail

There’s a question we need to be asking here, and that’s, What are we sacrificing when we value accelerated learning, as measured and judged within a narrow frame, above all else?

This is what I think we sacrifice: the time to build meaningful relationships with students, and even our colleagues. It is this which has significant implications for the chance of a school becoming a democratic space.

For when we go fast, with our eyes on results, we value the prize over the person. It really doesn’t matter who they are and what they want, because the point of school is to achieve, to accelerate, to extend …

“What gets measured gets done, what gets measured and fed back gets done well, what gets rewarded gets repeated.”

John E. Jones

We all know what’s measured, fed back and repeated. My kids’, your kids’, reports are Exhibit A.

We’re defining our kids and how they relate to the world not by who they are, but by how well they can do the things a school wants them to do.

It’s a recipe for compliance or defiance, for deference or dissatisfaction.

Jonathan Sacks, in his book Morality: restoring the common good in divided times, argues in the chapter on democracy that we have come to see it in terms of two sectors - the state and the individual - but this hasn’t always been the case. There is a third sector, he writes, saying,

“It is the third sector, civil society, that is seen as most vital to the health of democracy, because that is where we come together at a local level, forming moral communities where people help each other in face-to-face and side-by-side relationships, to do together what we cannot do alone. It is this area … that creates and sustains what Tocqueville … held to be the necessary ‘apprentiship to liberty’.”

It is my contention that if we want schools to become democratic spaces it is the cultivation of this third area that is required. And the key to creating that is in bringing the world of the student into a partnership with the world of the school.

When it happens at the moment, it is down to luck, and some kids are luckier than others, often as a result of their cultural capital which means their world closely mirrors that of the school world.

Sacks goes on to say,

“The state is about power. Families and communities are about people. They are about personal relationships and lifting one another from depression and despair. When these are lost from civil society, they cannot be outsourced to the state.”

This is a clear enough metaphor for schools, to my mind. Our education system has become a mini-state that exercise power over children. And so, because there is no third sector, achievement in the areas deemed valuable by the system is prized above all else.

Parents demand progress, and it’s the school’s responsibility. There is little in the way of partnership, of people helping side-by-side, because there is not a space for it.

No one really knows each other well enough for that to happen.

There is no way a democratic school can happen without time being given to the development of relationships that allow people to work together. It’s not about kids getting to vote or propose activities, or having a seat or voice on the board.

What needs to happen is for the two worlds that already exist to meet and create a third, shared, civil space.

The dreams, culture, skills, passions and expectations of the student can add real colour and vibrancy to this space.

Schools have much of value to offer our kids: curriculum expertise, experiences, connections. But these are only powerful if they are used in service of the world of the kid.

It’s a much less predictable way of schooling, with learning likely to venture off into many diverse paths. But it’s a much more life-affirming, liberty enhancing approach.

For when students are seen, and their ways of thinking and doing are valued and enriched by what school has to offer, their lives are changed.

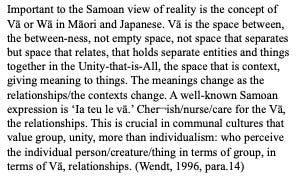

One idea that’s been running in the back of my mind as I’ve thought about this essay is the concept of Vä, which runs across Pacific cultures.

Now, this is a challenge for us, because we do view education as an individual pursuit. But, for anyone (except for hotshots) we are dependent on others in our learning. We learn from the past, from our encounters and experiences, from the relationships we have, just as much from access to knowledge.

Learning is communal.

There is a space between the learner and the school. It should connect, not be swamped.

When we don’t acknowledge this, when we don’t act to connect and nourish this third space, we act in the interests of privilege.

“To understand the importance of vä, one must view relationships as the most influential dynamic in shaping both individual identity and the nature of the social world. Therefore, it is within the context of relationship that self identity is formed and is continually affected. In addition, it is the nature of all of our interactions with others (on a much larger scale, the culmination of all relationships) that shapes the very nature of our society, either harmonious, indifferent or in conflict.”

Karlo Mila-Scaaf, 2006

What we’re talking about here is listening and understanding. We’re talking about relationships as negotiated entities that shape the society we live in. If we want our world to be harmonious, we need to actively work to create harmonious relationships.

Especially those of us who have power.

In schools, it’s easy to get swept into the world of learning as told by data. There are too many decisions made on those data sets that forget about the people behind the number. Too many of those decisions entrench assumptions and stereotypes about learning and learners.

Rowan Simpson writes about the danger of this from a software development perspective:

“How would we explain our design decisions to them, in person? Perhaps on a percentage basis they don't seem significant, and so are too easily overlooked, but it's more difficult to imagine standing in front of them and telling them to their face that they don't matter.”

Tell them to their face. Look them in the eye and explain why.

How many decision-makers in schools and education are looking kids in the eyes and explaining to them why (they can’t dance every day)?

How many board members who demand more direct instruction are taking the time to sit in the classrooms and see for themselves the impact of that?

This is the heart of democracy isn’t it: the powerful fronting, listening and working with those they are charged with helping.